WARNING! This article contains BLONDE spoilers.

When Joyce Carol Oates began writing Blonde, the 2000 novel on which the new Ana de Armas movie is based, she admitted she was less concerned with the facts of Marilyn Monroe’s life than the idea of the quintessential movie star. Oates saw Monroe as an emblem of 20th century America, a pivotal intersection of the nation’s values and fantasies about sex, power, and the role of women during a moment of cultural ascendence.

This also means that much of the work is fictionalized—which is a polite way to say made up. These details have lingered on the page where the clarity of Oates’ vision, and the persuasiveness of her prose, made Blonde a seminal work that was instantly recognized as a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award. However, those who’ve only read Oates’ novel might come away with a very different perception of Norma Jeane Mortenson, the woman who would become Marilyn Monroe, than what the historical record suggests.

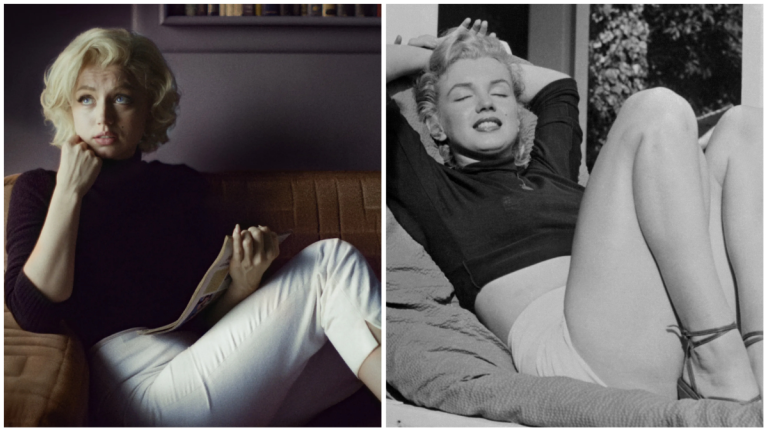

That line is about to be blurred much further with the release of Andrew Dominik’s movie adaptation of Oates’ novel. Immaculately crafted and deliberately opaque, the film provides a meditative and seemingly biographical portrait of Monroe’s life, with de Armas playing Monroe as both a fragile, wounded creature and an often hysterical, oversexed pawn who ran away from her natural desire to build a family.

Whether Netflix’s Blonde is an artistic success is open to interpretation, but below are some of the most shocking and scintillating revelations in the movie—and how they stack up against the facts of Monroe’s life.

Did Marilyn Monroe’s Mother Try to Drown Her in a Bathtub?

The real Norma Jeane Mortenson, born in 1926, came from a long lineage of mental illness. This is dramatized to viscerally horrifying effect in Blonde when as a child Norma Jeane is repeatedly beaten by and terrified of her single mother Gladys Pearl Baker (Julianne Nicholson). Eventually, on the night of a Hollywood fire, Gladys has a breakdown and tries to drown her daughter in the bath. Norma Jeane barely escapes her nude mother by running to her neighbors across the hall, Albert Wayne and Ida Bolender.

It’s the stuff of a horror movie—it also is a disservice to the real Gladys because Marilyn never claimed her mother tried to drown her. Blonde as both a novel and film conflates Gladys with her own mother, Norma Jeane’s grandmother Della Monroe. Like her daughter and (probably) her granddaughter, Della struggled with bouts of mental illness and depression. Marilyn later told a journalist that her first memory was of a smothering sensation when Della placed a pillow (or something similar) over her face while the child was sleeping. Marilyn’s third husband Arthur Miller later confirmed to biographer Fred Lawrence Guiles that Marilyn shared this story with him.

At the time, Marilyn would’ve been less than two years old when this occurred, but perhaps the trauma left a striking memory, as did what came later. One morning when as a young girl Norma Jeane was visiting her neighbors across the street, the real-life Bolenders, they began hearing banging on the door. It was Della, demanding Norma Jeane come back. She paced up and down their porch and banged the door so hard she broke a pane and cut her hand. The Bolenders called a police car, and Della was dragged away screaming.

Della Monroe was committed to the Norwalk State Hospital you see in Blonde where she died 18 days later of a seizure.

Did Marilyn Monroe’s Mother Keep a Framed Picture of the Missing Father on the Wall?

In Blonde, the image of Norma Jeane’s father is presented as something like the Rosebud sled in Citizen Kane. Her mother uses the photograph to brainwash Norma Jeane into believing that one day daddy will return and save them from their life of squalor.

In reality, the childhood of Norma Jeane was incredibly unstable, veering from some sense of normalcy, such as in one home where her mother bought a baby grand piano that Marilyn would hunt down later in life after it had been sold, to Gladys boarding Norma Jeane with the aforementioned Bolenders for several years while sending a monthly stipend for her daughter’s care.

Sadly, like her mother, Gladys struggled with depression and mental disorders, and was eventually committed to the same hospital where her mother died. However, unlike in the movie Blonde, Gladys did not die there, completely incapable of even recognizing her daughter. It’s actually because of Gladys, and not the Bolenders who are depicted onscreen as not wanting to get involved, that Marilyn ended up in an orphanage. After Gladys was committed, Norma Jeane eventually came to be in the care of a family who wanted to adopt the child and move to New Orleans. Gladys refused, as she did not want to lose her daughter, so Norma Jeane was institutionalized at an orphanage and, eventually, a series of foster homes.

Still, before she was committed, Gladys kept a picture of a man on her wall and told Norma Jeane it was her father: the photo was of Charles Stanley Gifford. What Blonde does not get into is that Gifford was not Gladys’ first husband—with whom she actually had several children before Norma Jeane. Married to an older man named Jasper Newton Baker when she was 15, Gladys met Gifford while working as a film cutter at Consolidated Film Industries in Los Angeles. Gifford reportedly showed no interest in helping raise a kid after Gladys told him she was pregnant—Jasper meanwhile left her and took their children out of state.

As a child, Norma Jeane would later tell her peers that her father was Clark Gable, who somewhat resembled Gifford and would later star opposite Monroe in the final film for both actors: The Misfits (1961).

For the record, Gladys first left her mental hospital after more than a decade of care there. She stayed with Norma Jeane in an apartment during World War II, although Norma notably moved to a studio club for ingenues to get away from seeing her mother everyday. Out of loneliness, Gladys eventually asked to be recommitted and would be in and out of hospitals for the rest of her life.

Marilyn Monroe and the Kennedys

Perhaps the most shocking scene in all of Blonde is when she is brought in to meet President John F. Kennedy—her inner-monologue rightly surmises it’s like a piece of meat being delivered—and he immediately forces her to perform oral sex on her. In extreme close-up, we study her eyes as she considers this surreal and nightmarish situation of being debased to the point of a concubine by the president.

From what we know, she likely did act as Kennedy’s mistress and paramour, and if so did it out of a sense of admiration for the young POTUS. What went on behind closed doors—and whether he physically abused and demeaned Monroe—is pure conjecture and speculation by Blonde.

Get the best of us delivered right to your inbox!

Get the best of us delivered right to your inbox!

Get the best of us delivered right to your inbox!

With that said, Marilyn might’ve slept with JFK, but the Kennedy she obsessed over was his younger brother and the attorney general Robert Kennedy. She visited Bobby repeatedly and made multiple calls to the Justice Department, some of which were logged by Bobby’s personal secretary. Marilyn even told a friend she was considering marrying for a fourth time, perhaps someone in politics and who lived in Washington D.C. This would seem to suggest she became infatuated with Bobby, because it would surely be delusion to think he’d torpedo his marriage and political career to marry a (thrice divorced) movie star.

There is also some contention whether Monroe had an abortion around this time. A publicist who worked with Marilyn’s press agent claims she had an abortion several weeks before her suicide, with biographers speculating it could’ve been either John or Bobby Kennedy’s unborn child.

Some also speculate that Marilyn even saw Bobby during the last few days of her life. Robert Kennedy was in California when she died, arriving at a small ranch 85 miles south of San Francisco the day before. The Justice Department document that records this has been noted as unusual since it details his arrival on a day when nothing else of official government business was scheduled or recorded. It simply states he spent the first two nights at the ranch before staying at a friend’s apartment in the city on Sunday evening. It’s miscellaneous, but conspiracy theorists will be quick to note it sure is handy as evidence he was nowhere near Los Angeles on the last weekend of Marilyn Monroe’s life.

Did Marilyn Monroe Kill Herself Because of Her Father?

As aforementioned, she was never actually catfished by a made-up son of Charlie Chaplin into believing she was having a profound correspondence with her “tearful father.” The real Charlie Chaplin Jr. did not even die before her—and therefore did not bequeath evidence that he manipulated her all these years because he’s some kind of cruel, evil fiend.

The truth is we’ll never know exactly why Marilyn killed herself other than she suffered from bouts of depression and loneliness, the kind which Arthur Miller has discussed at length of witnessing and trying to help her fight. Whether Bobby Kennedy ended things with her the day before or if she just had another empty weekend in her increasingly isolated lifestyle, perhaps also reflecting on her then dimming career since she’d also just been fired by Fox off a movie called Something’s Gotta Give, is anyone’s guess.

All that is certain is Marilyn Monroe, the woman who was born Norma Jeane, died of an overdose of sleeping pills on Aug. 4, 1962. She was only 36.